Dear Gentle Reader,

Dear Gentle Reader,The external walls of our apartment are, basically, windows.

This spells good news for potential defenestrators.

It also provides poor Pommes, your Hero, with a view on the world that he can no longer play in.

Depending on how long you have been visiting here, you have seen the title view of this post.

If I go a bit farther up my building, that view changes.

If I go a bit farther up my building, that view changes.One day I wondered what this building was.

Being a scribe, I went looking for what other scribes might have written and filed about this place.

It turns out that this is Signal Tower and that the outcropping of rock that it stands upon is called Blackhead Point.

In the heyday of frigates and clippers, in Hong Kong's early mercantile culture and history, Signal Tower was very visible and very important.

And, I discovered, the most important piece of Signal Tower was taken down for its constituent metal sometime after 1933.

Everyday at 1 pm, from 1907 to 1920, and twice a day, at 10 am and at 4 pm, from 1920-1933, a large copper ball, situated upon a tall, vertical rod mounted on the top of the building, was released and plunged down to the top of Signal Tower.

After this operation, the copper ball would be slowly winched back up to its resting place in time for its drop, again, the next day.

What was this big copper ball for?

It was a once-a-day (later a twice-a-day) timepiece that ships in the harbour could see and set their chronometers by.

Why was it there? First, a digression.

Hong Kong Island was won by naval arms. Hong Kong Island was ceded by treaty, in 1841, to Britain from China's Imperial Qing Dynasty Emperor.

Hong Kong not only relied on the British Navy for security and projected naval power, but, Hong Kong was the way station for opium on its way into China, and for goods, such as silver, gold, silk, and teas, on their way to Britain, Europe, and the Americas.

Hong Kong, though an International Free Port, nonetheless had many ways of generating revenue and profits off traders and it depended on international shipping which mean frigates, and, much later, steam vessels. And shipping vessels depend on knowing where they are, and what direction they have to head, to get to their markets to sell their wares.

Signal Tower might have been the third signal tower in Hong Kong. The Signal Tower near my house replaced a less visible signal tower on the Kowloon waterfront built in front of the Tsim Sha Tsui Police Station by 1884. I don't know when that tower was built, but Kowloon was not ceded to the British until 1860 after China's defeat in the Second Opium War

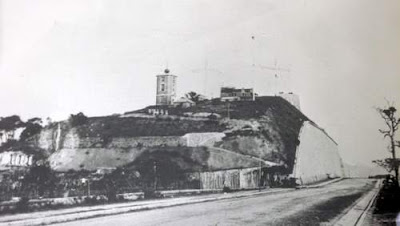

Signal Tower, on Blackhead Point, used to look like this, and you can clearly see the big copper ball on the roof...

So, why was knowing the time important? Why was this Signal Tower, with its time signal, important?

To note location, even today, on a map, people talk about the longitude and latitude of that location.

If you imagine the Earth as being a sphere with the North Pole pointing up, and the South Pole pointing down, then latitude are the horizontal markings that slice the world up.

[So the equator (latitude 0), the Tropic of Cancer (23° 26' 22" north of the Equator), the Tropic of Capricorn (23° 26' 22" south of the Equator), and the Arctic and Antarctic Circles (respectively 66° 33' 39" north and south of the Equator) are all latitude lines.]

For Reference, Hong Kong is just below the Tropic of Cancer.

Latitude (in the Northern hemisphere) was easy to calculate if you could find a star close to the North Pole. (It was also easy to tell if you could see the sun at high noon.)

Polaris, the North Star (the one which the handle of the Big Dipper points to), stays within 1° of the North Pole. So, mariners would use an astrolabe or a quadrant or a sextant or an octant to determine how many degrees the horizon was from Polaris (or, in the day, the sun at meridian height, but there is no need to get too technical here).

The number of degrees that the horizon would be from Polaris indicated to the mariner how many degrees of latitude north of the Equator she and her vessel were.

The difficult measurement for the mariner to make was longitude, which measures how eastward or westward you are on a map.

Longitude lines are the lines that cut the earth into vertical slices; all longitudinal lines cross through both the North and South Pole, so Polaris is not a good reference because they all longitudinal lines intercept it.

To determine longitude, besides a rather tricky and math and algorithm intensive lunar reckoning system, the mariner had to know the time. With the time, and a few simple readings, the mariner could easily work out where she was, and which direction she needed to sail in to get to her destination.

Each ship would have, for safety and redundancy, three ship's clocks to allow the crew (or rather one, designated, privileged Master Mariner) to tell the time and work out how far east, or west, around the globe they were on the travels.

The ship's three clocks were kept in bottles, on gimbals, in the heart of the ship to protect them from the elements and the motion of the sea and the ship.

But, still, the duress of life at sea, and the shocks of repeated hits of waves on the bow and sides of the ship, was rough on timepieces, and chronometers necessary for voyages measured in months needed to be checked for accuracy.

Many coastal cities have daily guns, but light travels faster than sound, and that is why Hong Kong had the big brass ball on Signal Tower at Blackhead Point.

Not so witty or pretty, but I look at this tower everyday, and now I finally know its purpose and import. Which is good enough for me, today.

Tschuess,

Chris

Containers that are not filled with goods to be shipped frequently end up in Tuen Mun, a suburb city of a half million people outside of Hong Kong.

Containers that are not filled with goods to be shipped frequently end up in Tuen Mun, a suburb city of a half million people outside of Hong Kong.![Under the spreading chestnut tree, I sold you and you sold me. (Heard over the radio in the last pages of 1984, George Orwell [a.k.a. Eric Blair]) Second image of stacked, empty containers in Tuen Mun, Hong Kong.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgAel7fXrpHmOt8yM3zMFlgAg1P6i1St8hLtvI8gzVxgJ1ce0sQX2mUvn-MNGdG5pTDRBSIO7lYnatXKe_dM3Kuiu2Fu_hNa4LybEcHyPCkFeWbIH_I5RaxeGJKR-f1fmQe4bgY7-IatG1E/s400/PICT0073.JPG)