Dear Gentle Reader,

In today's first post, possibly the more interesting one, I talked about feeling the weight of air in India.

Then Junosmom posted a picture of air that showed air's ability to move things, which is indirect proof of air's weight (more properly, air's mass).

The historical weight of air is an interesting (to me) journey in science and philosophy.

If you're game, let's take a quick ride.

First, we need to look at the idea of nothingness and then we can move to air.

Which makes sense, as air is commonly seen (and felt) as nothing, no?

Democritus (c. 460- c. 370 BC), the Laughing Philosopher, is considered the Father of (modern) Science.

Democritus proposed the first particle theory of the universe and was an atomist, a determinist, and a mechanist.

Democritus believed in indivisible atoms being the building blocks of the world and he also believed in the existence nothing; Democritus believe that a vacuum could exist.

Previous Greek philosophers had grappled with the idea of nothing, and concluded that nothing, a vacuum, was impossible as nothing, by definition could not exist.

A nothingness could not be a thing, they reasoned, so it could not exist.

Some philosophers argued that motion requires the creation of a vacuum, which cannot exist, and therefore they said motion cannot exist. (OK, Zeno of Elea (490?-430? BC) and his teacher, Parmenides (early 5th century BC), said this, though they were known for their paradoxes.)

Democritus chuckled and retorted that he observed motion, therefore, if motion required a vacuum, then vacuums must exist--regardless of the arguments against vacuums in the minds of men.

Democritus was not concerned with teleology (what purpose did the event witnessed serve?) and was therefore scorned by Aristotle (384-322 BC), the first natural philosopher and the preeminent scientific reference through the medieval ages.

Democritus was concerned solely with what he observed and what made those observations so.

For Aristotle, teleology, the underlying purpose or ultimate effect, was paramount.

For Aristotle, it was observations that were unnecessary.

Aristotle felt the real world should conform to an ideal world and that observed facts were secondary to mentally revealed truths.

This viewpoint made Aristotle very appealing to medieval theologians and lawyers (the school of scholasticism).

As Aristotle gained prominence in theology and law, so he gained prominence in science, as conceived in the medieval world--all thinking, no testing.

Until the Scientific Revolution, starting in the late Renaissance and extending to the Age of Enlightenment, Aristotle was science.

Further, people and ideas whom Aristotle had rubbished, like Democritus and the idea of a void existing in nature, ...were also rubbished.

For example, Aristotle came up with two laws of motion, in his version of physics, worked out by thinking, not by experimentation.

Aristotle's first law of motion was that the speed of a falling object is proportional to that object's weight; heavy things fall faster than lighter things.

Aristotle's second law of motion was that the speed of a falling object is inversely proportional to the density of the object it was falling through; things can't fall through solids and things would fall infinitely fast in a void.

Nothing, of course, falls infinitely fast, therefore voids do not exist.

That is Aristotle, on motion, in a nutshell.

This was why Galileo Galilei's (1564-1662) alleged experiment of the two balls, of differing weights, being heaved off the side of the leaning tower of Pisa and falling at the same speed was such a big deal.

Galileo was an experimenter who stated that the observed was more important than an independent theory, and that theories had to reflect reality; reality couldn't be ignored to suit a theory.

That, of course, was why Galileo Galilei was put under house arrest by the Church in 1634.

The Church had stated that the Earth was the centre of the universe as Man was the centre of God's creation.

Galileo observed the motions of the planets and the heavens in his telescope and, eventually, screwed up the nerve to note that it appeared that the earth revolved around the sun, not the other way around.

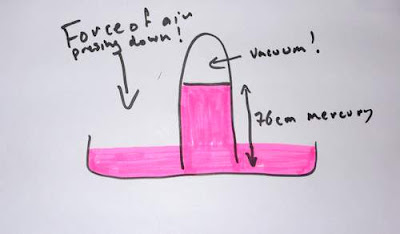

Then, in 1644, two year's after Galileo's death, came Galileo's student, Evangelista Torricelli (1608-1647), and his experiment in Florence, Italy, which proved that nature didn't abhor a vacuum; a great nail in Aristotle's coffin.

What was this experiment?

Torricelli filled a long (1 metre or 3 foot) test tube with mercury.

He then capped it with his thumb and upended it into a pan filled with more mercury, with the test tube bottom facing the sky and the open end, capped by his thumb, under the surface of the mercury in the pan.

Torricelli then removed his thumb and some of the mercury in the test tube drained down into the pan, leaving a vacuum behind it in the top portion of the test tube.

But, the Mercury did not drain down completely.

76 cm of mercury remained in the test tube.

What held that 76 cm of mercury in the test tube?

The weight of air, pressing down.

And what filled that 24 cm of space in the top of the test tube, where the mercury had been but was not anymore? Nothing!

Nature, it turned out, does not abhor a vacuum. In fact, it was rather easy to make a vacuum.

Nothing, philosophically, was very substantial.

And, air had weight.

Revelation upon revelation!

And this revelation, for Aristotle, would be apocalyptic for his supremacy in science.

Even Galileo Galilei hadn't bothered to consider whether air could have weight, it was just obvious to him that air had no weight.

(Of course your humble scribe could have told you that air has weight, that first night in India, as the hot, heavy threatened to push me onto the ground, but I digress.)

Torricelli had disproved Aristotle, opened up a whole new world of experimentation, and vindicated his teacher, Galileo Galilei by demonstrating the power and necessity of experimentation.

As regards to the weight of air, in his notebook, Torricelli wrote that "we live submerged at the bottom of an ocean of elementary air, which is known by incontestable experiments to have weight".

What a radical idea.

Natural philosophers (scientists) across Europe raced to duplicate Torricelli's work (he had, you may note, invented the barometer) with mediums of different densities (mass per unit volume).

These other scientists wanted to see if air really did have weight, if that weight was the same everywhere, if that weight differed by altitude (as you would expect), or if there was something peculiar going on with mercury and Italy.

In France, the eminent mathematician and physicist, Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) heard about Torricelli's experiment in 1646. (News travels slow if it is walked across the mountains.)

Blaise Pascal had a relation who was a vintner--a winemaker.

Blaise and the vintner duplicated Torricelli's experiment with wine and a giant bottle (a mega-test tube). Blaise Pascal's bottle was over thirty feet long.

Blaise and the vintner replicated Torricelli's experiment with wine in the hills of France, above the fields of grapes; the experiment worked.

Air definitely had weight and it pressed down on us from the heavens above.

After the experiment Pascal and his relation drained the bottle.

All 33 or 34 or 36 feet of it... (I forget and I am not doing the calculations now. Sorry.)

And then, after quaffing all that wine, Blaise and his vintner relative suffered "religious" visions--at least that's what they thought...

When Pascal's father nearly died that winter these two events drew Pascal to Jansenism, a branch of Roman Catholicism, and Blaise became a religious philosopher, abandoning science for religion.

(This conversion of course brings the revolution of the column of air full circle, from belief (that air had no weight) to experimentation and back to belief.)

All of the above was rushing through my mind, in the time of the shadow, as I attempted to stand under the weight of hot air on the airport tarmac in Mumbai, India, upon my arrival.

Thinking through this, waiting on the tarmac and then waiting on my luggage, was my puja to the world.

Tschuess,

Chris

4 comments:

The experiments of the ancients made so much sense---they still do. When the heat and humidity of summer in NE OH weigh me down, I will remember that they do weigh me down.

Dear Debra,

It's not just good for breathing, its good for thinking about. Torricelli's final experiment finally made it acceptable to be an experimenter in Europe if you investigated science and showed that Aristotle, while a fine thinker, was not anywhere near as right as he thought he was.

Tschuess,

Chris

My little photo spurred this? I will have my girls read it and count that as science for today!

Dear Junosmom,

The heat brought it on, your photo brough it out. Worth a thousand words, no?

Tschuess,

Chris

Post a Comment